JACQUES-PHILIPPE LESUEUR

(Paris 1757-1830)

Model for the Tomb of Jean-Jacques Rousseau

On the Île des Peupliers in Ermenonville

Patinated terracotta plaster mold

27 x 37 x 16 cm

Signed and dated : Le Sueur 1780.

PROVENANCE: Probably Paris, Salon of 1791, no. 460 Modèle, en plâtre, du tombeau de JJ Rousseau, tel qu’il est exécuté à Ermenonville (?); private collection, France

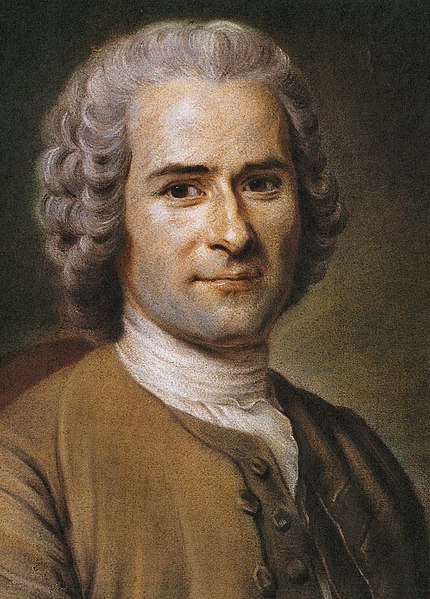

The plaster model for the tomb of Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) is a reminder to us of the friendship between the philosopher and the Marquis de Girardin (1735-1808), grand seigneur, patron of the arts and passionately interested by the beauty of all things rustic, most importantly, garden.

Philanthropist, liberal aristocrat and an admirer of the Encyclopedists, Girardin—working with the painter Hubert Robert and the gardener Jean-Marie Morel— spent over fifteen years creating a garden on his property in Ermenonville (50 km north of Paris, close to the Abbaye Royale de Chaalis). This English garden stretched over more than forty hectares (out of the 950 of the estate), and it was here that he applied his principles of creativity.

Fascinated by the large gardens on the other side of the Channel, like Stowe and Blenheim, Girardin elaborated his ideas in his work, De la composition des paysages sur le terrain ou des moyens d’embellir la Nature près des habitations en y joignant l’agréable à l’utile. In it he declared, “It is thus neither as an architect, nor as a gardener, but rather as a poet and a painter that landscapes should be composed, in order to interest both the eye and the mind.”

He distanced himself from Le Nôtre’s principles and the too-strictly ordered landscape of the jardin à la française, appealing to visitors as an artist, encouraging in them a taste for the picturesque romanticism of his compositions.

Numerous follies, sometimes bearing philosophical inscriptions, were to be found as one walked about the grounds, while in the distance, gaps in the woodlands gave glimpses of the village of Ermenonville or of neighboring monuments, like the Abbaye de Chaalis and the dungeon at Montépilloy.

In the north part of the park were houses for farm workers and the pastures that they shared, giving Girardin’s creation the social dimension so dear to this admirer of Voltaire, Descartes and Montesquieu, poles apart from the frivolous atmosphere that characterized Marie-Antoinette’s Petit Trianon at the same period.

Julie ou la Nouvelle Héloïse, the epistolary novel by Rousseau (1761) describing a garden owing everything to Nature, was Girardin’s inspiration for Ermenonville.

In view of this, when the philosopher Rousseau, “all alone in the world,” was again looking for refuge in the country, it was in Ermenonville, at the invitation of the Marquis, that he settled with his companion, Thérèse Le Vasseur. There he was enthusiastically reunited with the Nature that was so dear to his heart: “Ah, sir!” he said, throwing his arms around my neck, “my heart has so long yearned to return here and my eyes make me want to stay forever.” Far from the tumult of the city, Rousseau relaxed, collecting plants, giving botany and singing lessons to local children, and enjoying the isolation of a cabin in the park. But on 2 July 1778, some weeks after his arrival, he fell victim to a stroke and died during the day.

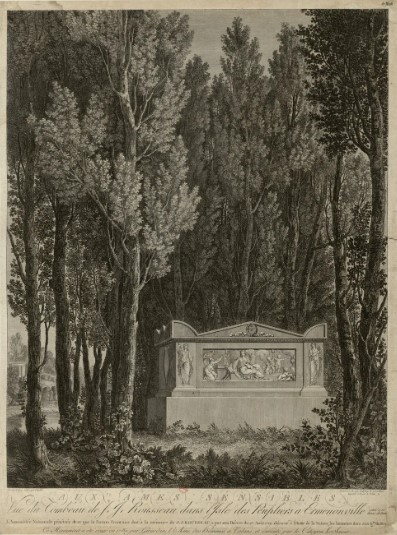

He was buried by torchlight on 4 July on the Île des Peupliers, at the heart of the park and clearly visible from the château, in a temporary tomb surmounted with a funeral urn (as seen in a print by Moreau le Jeune)

Girardin later commissioned the painter Robert to draw the design of the tomb which the sculptor Le Sueur—a young prodigy of 20—was to do in seventeen months, finishing it in 1781 (see G. Wick “Le tombeau et le jardin de la mémoire,” in Hubert Robert et la fabrique des jardins, 2017, pp. 101 & 104).

Girardin was aware that the tomb would be a place of pilgrimage for decades and centuries to come, and thus chose a monument whose shape and style would transcend the period. Robert drew on the most exhaustive collection of Classical forms, Le Antichità romane by Piranesi, for the simple monument: a square sarcophagus decorated with acroterions, inspired by an engraving illustrating the tomb of Nero.

Stanislas Girardin, in “Promenade ou Itinéraire des Jardins d’Ermenonville” (Paris, 1788) reproduced the engraving by Godefroy and described the monument, pp. 26 & 27 .

A few years later, in 1799, the memorialist Thiébaut de Berneaud described the tomb in these terms in his Voyages dans l’île des peupliers: “At the foot of a palm tree, symbol of fecundity, a woman sits, one hand holding her nursing son, and the other holding Emile, open to the spot where Rousseau, addressing wives, exhorts them so eloquently to be mothers. Not far away, Gratitude places an offering of flowers and fruit on the altar of Nature…Children play on the lawn nearby…On the two sides of the bas-relief are the attributes of the Music of Eloquence. Above there is a civic crown. On the other side, between the attributes Charity and Truth, can be read: Here rests a man of Nature and of Truth. In the tympanum, two doves expire on smoking torches.”

A single other model, undated and in very precarious condition has come down to us. It belonged to the Marquis de Girardin, who was given it by Le Sueur. As with the whole of his collection, it is today in the Abbaye Royale de Chaalis. This reinforces our conviction that this could not be the model exhibited by Le Sueur at the Salon 11 years later.

Our model, signed and dated 1780, was probably kept by the young sculptor as a testimony of his prestigious commission, and exhibited by him the first time he participated in the Salon, in 1791.

This commission was one of the first that Le Sueur received.

After winning the Premier Grand Prix de Rome in 1781, he went to Italy, multiplying public and private commissions upon his return to France. He worked for the financier Beaujon, owner of what is now the Palais de l’Elysée, and for the Châteaux of Saint-Cloud and Chantilly.

Under the Empire and the Restauration, he was awarded the patronage of the State and worked on the Panthéon and on reliefs for the Arc du Carrousel du Louvre (fig. h). He also received commissions for statues for the Palais du Luxembourg and the Pont Louis XVI.

Even though he had spent only six weeks in Ermenonville, the tomb of the Geneva philosopher made his host somewhat famous, along with the emblematic work by Le Sueur that symbolized the former. Marie-Antoinette, Mirabeau, Robespierre, Goethe, Bonaparte, Franklin and many others came to pay their respects before the monument, in the melancholy shade of the poplar trees.

During the Revolution, despite his openly liberal penchants, Girardin owed his safety only to the friendships he shared with a few Jacobins, among them Marat.

The tomb became a cenotaph when the remains of Rousseau were removed to the Panthéon, on 9 October 1794, after a decree voted by the Convention. The Marquis had to be separated from his friend in order to be raised up “from the stain of his aristocratic origins.” He then abandoned public life and only rarely stayed in Ermenonville.

A native of Geneva, with no influence or fortune, Rousseau moved to France, converted to Catholicism under the influence of his benefactress, Madame de Warens, and developed friendships in powerful circles of aristocratic liberals and among the Encyclopedists. He wrote Le Contrat Social, advocating the exercise sovereignty by the people, which would serve as the basis for the Déclaration des Droits de l’Homme and influence the political ideas of the French Revolution.

In Émile ou de l’Éducation, he called for education based on experience, and a profession of religion without dogma. Attacked by Voltaire and feeling himself to be the victim of persecution, he sought refuge among his friends, with the Marquis de Girardin among his closest.