LE MAÎTRE DES CORTÈGES

(Active in Paris, mid-17th century)

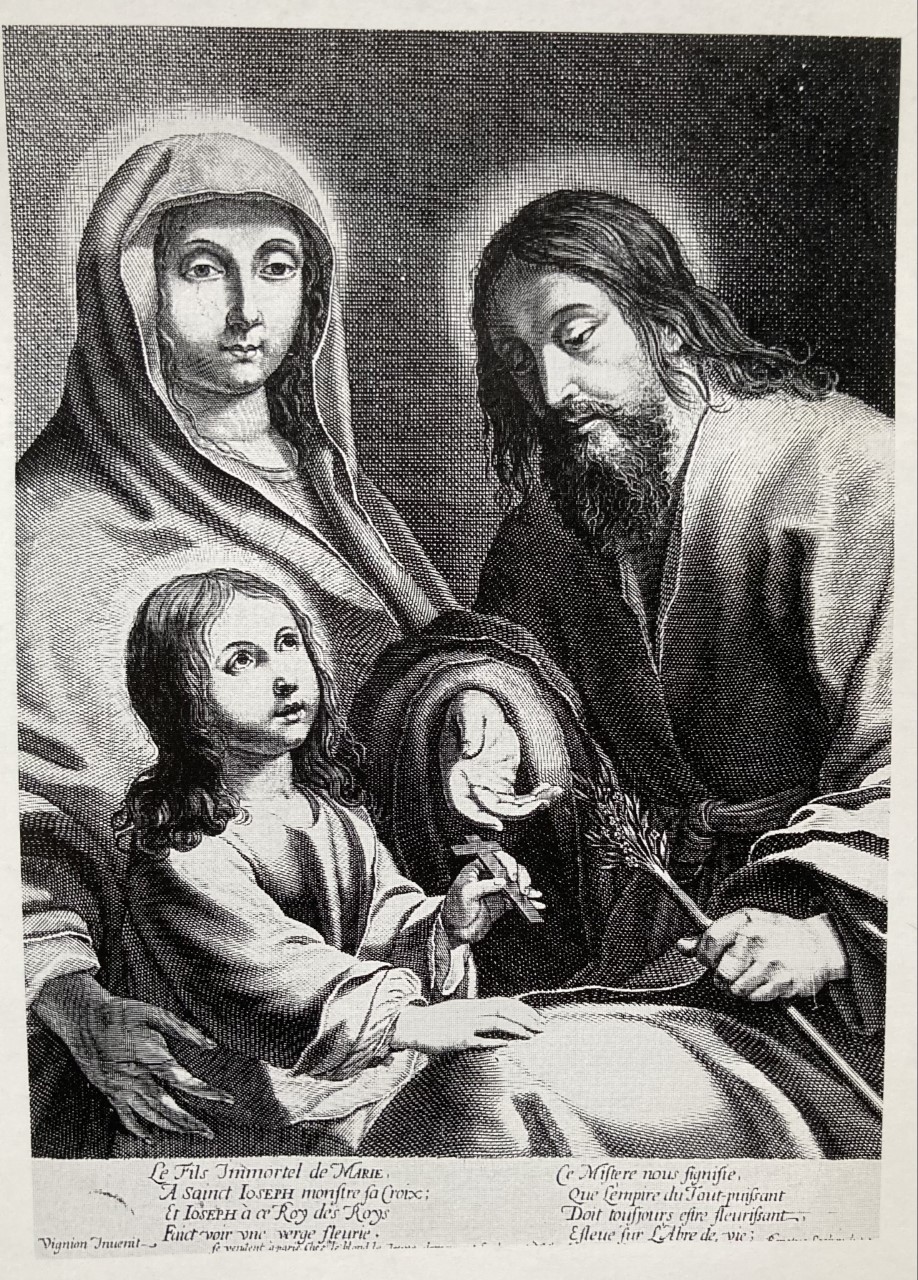

The Holy Family

Oil on copper

37.5 x 32 cm

Framed: 48.5 x 40 cm

PROVENANCE: Private collection, Eastern France

ENGRAVING: engraving by René Lochon in 1643

During two exhibitions in 1934 (Les peintres de la réalité at the Orangerie and Les frères Le Nain at the Petit Palais), Procession with an Ox (Paris, Musée Picasso, fig. 1) was one of the paintings that drew the most commentary. Picasso admired it enough to make it the only major old master work in his collection. When Longhi and Sterling began to express doubts about its attribution to the Le Nain brothers as early as 1930, a picture began to emerge of an artist working in Paris in the years 1630/40, sensitive to various influences—for some Italian, for others Scandinavian, and still others Eastern France—to whom there are fifteen or so compositions attributed today, some of which exist in several versions. By convention and for convenience, this figure is known as the Maître des Cortèges.

In his notes for the exhibition catalogue for Les frères Le Nain (Paris, Grand Palais, 1978-1979, pp. 330, 331), Jacques Thuillier described some of the elements that are characteristic of his artistic personality: “Colors reveal themselves to be very delicate, with nuances of grey and brown usually set off by large areas of red or bright blue.

The layout of the composition is always carefully studied, and often strikingly original…” Longhi, in a few limpid lines, wrote, “of an artist who would have served as a model in the circle of the Le Nain brothers, a kind of Vallotton, his art measured, with a slightly cold reserve, his compositions peopled with figures whose appearance is noble and distant.”

We can add a certain number of traits found in the various paintings by the Maître des Cortèges that seem to characterize his figures: long and sometimes hooked or slightly pointed noses, eyes deep-set in their sockets, the corners of the mouth clearly marked by shadow, silky hair, its details elaborated with particular care, and smooth complexions. Round, sometimes baby faces, feature serene and impassive expressions. The moderation of gesture and intensity of expression, like that seen in the Virgin in our painting, suggests, it seems to us, the culture of Holland or Northern France.

The weighty drapery, executed with creamy smooth brushwork in glowing colors—at times warm and sometimes almost metallic— clothe figures solidly anchored in simple, skillful compositions.These elements can be found as often in his sacred as in his secular works, as seen in Cortèges or Porters Fighting at the Pushkin Museum in Moscow.

Painted on a copper plate and until now in a collection outside Paris, our Holy Family is an important addition to the artist’s limited—but more and more cogent—corpus.

After the acquisition by the Louvre of Christ Crowned with Thorns (RF 2002-13), Jean-Pierre Cuzin was able to take stock of what is known about this original figure of the Parisian artistic scene of the mid-century. Even if their quality and dimensions are sometimes quite different, he emphasizes the identity of form and mind-set in the artist’s religious works, all painted—with one exception—on metal. To the painting at the Louvre, must be added Assumption at the Musée des Beaux-Arts of Rennes, The Adoration of the Shepherds (Berlin, Alte Nationalgalerie, the Crucifixion with Saint Mary-Madeleine (private collection) and Christ Carrying the Cross, also in a private collection.

The attribution of our Holy Family to the Maître des Cortèges was reinforced by direct comparisons with The Assumption at Rennes and the Christ Carrying the Cross, which proved totally conclusive.

The way Saint Joseph’s hands are positioned in relation to one another, quite similar to one of the tormentors in the Christ Crowned with Thorns at the Louvre, or the Mary-Madeleine in the Crucifixion; the tapering fingers of the Infant Jesus are seen again in the Christ in Christ Carrying the Cross, while thefeatures of his face and his hair are identical to the hangman placed at the extreme right of the Crowning. In addition to the drapery and color choices, these are some of the numerous points of similarity between these different compositions.

The existence of an engraving by René Lochon, dated 1643, replicating with perfect exactitude but inversely, the composition of our work on copper, and bearing in the margins the mentions “Vignon Invenit” and “Renatus Lochon lutetianus fa. / 1643” provides us with insight into the circumstances of the creation of the composition. A painting of relatively large dimensions (fig. 8, 122 x 93 cm), noted in 1878 as being at the Église Saint-Paul-Saint-Louis in Paris and today at the Église Saint-Joseph in the same city, which in all likelihood is the work of Claude Vignon (Paola Pacht Bassani, Claude Vignon, Arthena, Paris, 1993, n. 356, p. 391), can be regarded as the model that served for our composition.

While the composition is identical, the facture is radically different: the wide, burnished brushwork characteristic of Vignon’s mature work, and the summary, almost disintegrating, forms of the figures—which the rather mediocre state of conservation may explain—can in no way compete with the meticulous, perfect finish of our work on copper, whose enameled surface brilliantly transmits the richness of the fabrics, the softness of the flesh, and the iridescence of the halos.

All this notwithstanding, it appears certain that Lochon based his work on our work on copper and not on Vignon’s painting, even though the engraving is marked with this name in its margin inscription. From this, it is possible to imagine that the engraver commissioned our painting to reproduce it more easily. It might also be possible that the name Vignon at the bottom of the engraving is not that of Claude, the father, but of one of his numerous children who reproduced the same image in a small format. This double collaboration with Vignon and René Lochon, (for whom Maxime Préaud gives a plausible birthdate of around 1620), also allows us to definitively link the Maître des Cortèges to the Paris art milieu. The chronological point of reference furnished by the engraving represents a fundamental advance in our knowledge of the work of the Maître des Cortèges, allowing us to situate it with certitude before mid-century, five years before the death of Louis and Antoine Le Nain in 1648. It also confirms the dates advanced by the group of historians who have worked on the artist’s corpus.

All of these elements allow us to lift another piece of the veil that still hangs over the mystery of the identity of this profoundly original contemporary of the Le Nain brothers.

From the point of view of its iconography, two attributes are present in the middle of our composition: the cross held by the infant Jesus, a prefiguration of the Passion, and the flowering branch, a symbol of rebirth, held by Saint Joseph in answer response to it.

Joseph’s flowering branch also reminds us that God chose him to be Mary’s husband, and that this branch signifies His choice.

We are grateful to Pierre Rosenberg, Jean-Pierre Cuzin and Guillaume Kazerouni, for their generous assistance in the writing of these notes.